Vascular Access

Latest News

CME Content

As infection preventionists (IPs), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s Guidelines for the Prevention of Intravascular Device Associated Infections have long served as the cornerstone of much of our policy development. When the SHEA/IDSA Compendium documents were released those too served as a source of guidance. What sometimes has been overlooked have been the Infusion Nurses Society standards which were updated most recently earlier this year and currently reflect the latest evidence based recommendations for all aspects of infusion therapy across all disciplines involved. To keep moving the needle beyond the status quo we need to expand our involvement beyond just hand and skin antisepsis (an over simplification of our role!) and help with all aspects of vascular access and infusion therapy to impact the overall quality of care for these prevalent devices.

Earlier this year, one of the most widely used resources guiding clinical practice for the infusion specialty received a major upgrade. The Infusion Nurses Society (INS) issued a revised Infusion Therapy Standards of Practice, incorporating five years’ worth of new data to establish the most current, evidence-based best practices in vascular access.

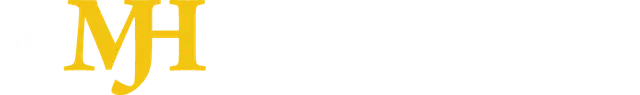

Central venous catheters (CVCs) play an integral role in healthcare, however studies have shown that they are among the most frequent cause of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs). Their use is associated with a risk of bloodstream infection caused by microorganisms colonizing the external surface of the device or the fluid pathway when the device is inserted or in the course of its use. The Joint Commission’s CLABSI Toolkit notes that “Employing relatively simple evidence-based practices to reduce, if not eliminate, CLABSIs appears to be within the reach of even resource-limited settings. Within this framework, HAIs-and CLABSIs in particular-are more and more being viewed as ‘preventable’ events.”

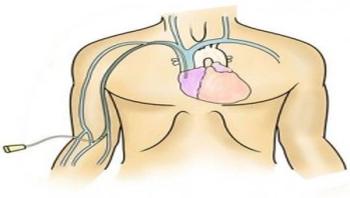

Every day, patients around the country get IV devices placed in their arms, to make it easier to receive medicines or have blood drawn over the course of days or weeks. But these PICC lines also raise the risk of potentially dangerous blood clots. Now, a University of Michigan Medical School team has shown how serious that clot risk really is for hospitalized patients, and what factors put patients at highest risk.

When it comes to improving patient and healthcare safety, many factors are considered: time to treatment, antimicrobials and increased reporting standards to name a few. However, a small device the needleless connector for intravenous systems can have a big impact, particularly on protecting healthcare workers from needlestick injuries and in reducing bacterial contamination. There are numerous options for these devices, and there may be confusion on current guidelines, as well as protocols for appropriate disinfection and use. With all the variables and increasing time constraints, how can healthcare professionals such as critical care nurses and infection preventionists improve patient care and safety, as well as protect themselves? By understanding the differences between the device options, healthcare professionals can more easily tailor their patient care, improve adherence to clinical best practice and ensure their safety.

Infection Control Today invited manufacturers to share their perspectives on the most critical aspects of vascular access-related infection prevention.

Nancy Delisio, RN, had a frightening phone call from a nurse who was trying to insert a PICC line. The line wasnt threading correctly, so she was calling us, says Delisio, a nurse educator with the Infusion Nurses Society (INS). What was she doing inserting the line, and where was her supervisor or another (trained clinician) to help her? That question illustrates a common theme among many calls INS receives. Bedside nurses dont know the basics something that needs to be taught from the top down. It leads me to believe that maybe staff nurses have heard about a procedure or protocol, but theyve never received appropriate training. Its the small things that lead to problems, Delisio says.