News

Infection surveillance, once the primary task of infection preventionists (IPs), has transitioned over time to assume a more limited place in a massively expanded scope of IP responsibilities. Infection surveillance data is used to measure success of infection prevention and control programs, to identify areas for improvement, and to meet public reporting mandates and pay for performance goals.

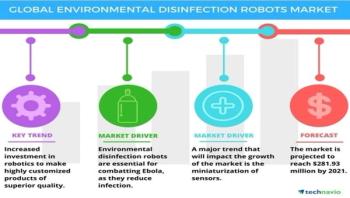

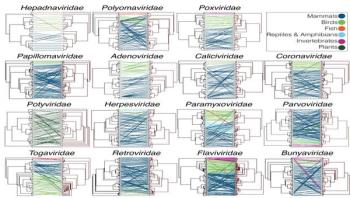

Vaccines and antimicrobials have done more to transform medicine and extend the average human lifespan than any other scientific breakthrough. Yet infectious diseases remain the world's No. 1 leading cause of death of children and young adults. Now, with emerging epidemic threats like Zika, Ebola, SARS, TB and others, massive increases in antimicrobial resistance, and the time and cost for developing new antimicrobial drugs and therapeutics, scientists are worried about finding ever new ways to outpace infectious diseases. One exciting approach to address this problem is the use of predictive tissue culture models that can more accurately reflect how our own bodies respond to pathogens.

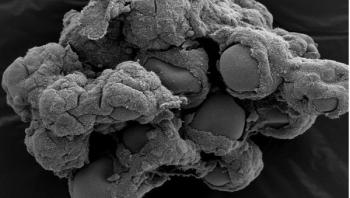

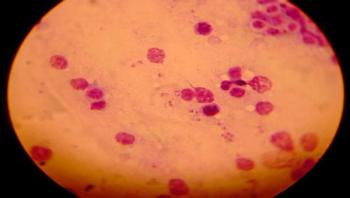

Leishmaniasis, caused by the bite of a sand fly carrying a Leishmania parasite, infects around a million people a year around the world. Now, making progress toward a vaccine against the parasitic disease, researchers reporting in PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases have characterized the structure of a protein from sand flies that can convey immunity to Leishmania.

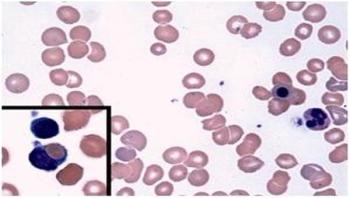

Babesiosis is a rare -- but increasingly common -- disease spread by ticks. After a bite from an infected tick, microscopic malaria-like parasites are transmitted into the host where they can infect and destroy red blood cells, causing nonimmune hemolytic anemia. Treatment with antimicrobials usually clears the parasite and resolves the anemia. However, sporadic cases of warm-antibody autoimmune hemolytic anemia (WAHA) have been observed in patients after treatments for babesiosis. This autoimmune form of anemia occurs when the body attacks its own red blood cells, eliminating these cells from circulation. To better understand this complication, BWH researchers led by Ann Wolley, MD, and Francisco Marty, MD, of the Division for Infectious Diseases at Brigham and Women's Hospital conducted a retrospective analysis of patients who had been cared for at BWH from January 2009 through June 2016. Of 86 patients diagnosed with babesiosis during that time, six developed WAHA two to four weeks later, after the parasitic infection had been resolved. These six cases are presented in a study published online in the New England Journal of Medicine on March 8.