Perhaps now is the time that innovation begins to rely more heavily on infection preventionists and our valuable insight into the world of healthcare PPE. The changes we help guide now, can help make healthcare safer and infection prevention easier.

Saskia v. Popescu, PhD, MPH, MA, CIC is an infection preventionist and infectious disease epidemiologist. Currently, she serves as a senior fellow at the Council on Strategic Risks, where she works to address global health security issues, including national policies impacting health care readiness and biodefense. Saskia is also an assistant professor at George Mason University, teaching courses on health care preparedness and epidemiology in policy. She holds a PhD in biodefense from George Mason University, where her research focused on the political and economic obstacles to investing in infection prevention, a MPH in infectious disease epidemiology, a MA in international security studies--both from the University of Arizona. Prior to her work at CSR, Saskia helped lead global health response at Netflix and was a senior infection preventionist with HonorHealth in Arizona. She has worked with the WHO, supported multiple NASEM workshops and reports, and supports NGO engagement within the Biological Weapons Convention at the UN. Saskia’s work is on building health care biopreparedness and readiness for infectious disease threats, especially in larger global health security efforts.

Perhaps now is the time that innovation begins to rely more heavily on infection preventionists and our valuable insight into the world of healthcare PPE. The changes we help guide now, can help make healthcare safer and infection prevention easier.

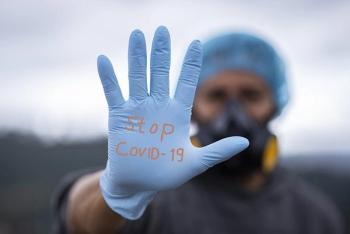

Simply put, a single approach strategy, like the test-only approach within the White House, is one doomed for failure. Meanwhile, the CDC updates what it means by an airborne transmission of COVID-19.

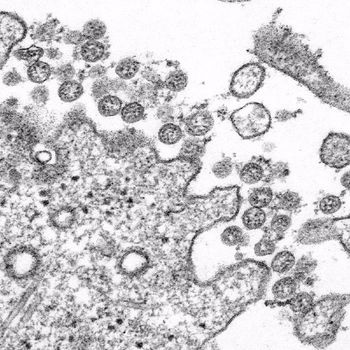

The means of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and the age group most likely to transmit the virus—people in their 20s—garnered headlines this week, as well as controversy for the CDC.

Most hospitals have implemented stringent visitor restrictions that don’t allow anyone to visit, even during end of life. While an understandable public health and infection prevention measure, it has generated some concern.

As these healthcare worker serology studies are designed and performed, we need more insight beyond just PPE use and symptoms, but also internal and external exposures.

The CDC released new guidance regarding recommendations for post-exposure COVID-19 testing. Here’s what this means for infection preventionists and public health.

Will it be a severe flu season? Will SARS-CoV-2/coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) surges occur this winter? How will this compound the stresses of COVID-19?

Knowing the needs of patients, how can we safely allow visitors again? When will universal masking not be required? A piece to this is that there is no hard rule. These are conversations that require considerable collaboration and plans to scale up and scale down.

Neck gaiters weren’t the only face coverings tested: in all 14 were analyzed, from N95s (unsurprisingly judged to be the most effective in containing COVID-19 spread) to bandanas (not much more effective then neck gaiters, according to the study).

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to surge, it is unlikely that contact tracing within healthcare will become anything less than critical.

The concern is not only that COVID-19 significantly increases the burden to healthcare facilities during an already busy season, but that the potential for more testing in patients with non-specific respiratory virus symptoms could further strain testing capacity.

Many patients in the study who did not require hospitalization experienced prolonged or persistent symptoms, nonetheless. In addition, the absence of underlying medical conditions does not automatically mean patients will not experiences these longer lasting symptoms.

Supply chain issues are a larger, more systemic aspect of healthcare and national preparedness. Although IPs may not be able to fix them individually, there are ways we can ensure the safety of our hospitals.

We have much work to do in terms of risk communication and awareness. This is a good example of how quickly exposures can happen in the workplace when we focus only on employee-to-customer interactions or healthcare worker-to-patient interactions.

One news item: Hospitals will now be reporting COVID-19 information to the National Guard instead of to the CDC through the TeleTrack system within the Department of Health and Human Services.

There is a desperate need to infuse SNFs with more resources, not only in terms of personal protective equipment, but also the critical infection prevention resources and staffing.

It’s when infection preventionists leave the hospital or go to get a coffee in the cafeteria, that behaviors can become lax. We opt to take breaks from masking, exhausted from it all.

While the rest of the hospital bustles with energy as healthcare workers fight COVID-19, emergency departments have been oddly quiet because of the drop in elective surgeries.

Those of us in healthcare and infection prevention must focus on sustainable efforts to combat COVID-19. How do we maintain readiness and response without burnout? There’s no solid answer to this, but a big piece really goes into the establishment of plans and education.

In many cases, the relationship between IP and the supply chain department is passive and fluctuates with emergencies or new products. What if, though, we worked to have a more proactive relationship that involved weekly meetings regarding the level of supplies, like PPE?

IIn the latest Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), researchers discuss SARS-CoV-2 in two domestic cats.

Infection prevention sustainability isn’t easy and everyone is exhausted, but now is the time that practice makes permanent.

Small clusters of environmental transmission in gyms and other workout settings can tell us about potential risky environments in healthcare. Outpatient physical therapy for one.

For those working in healthcare, the relationship with the supply chain department was an increasingly important one. Between daily mask utilization and supply reporting to scrambling to find more supplies, those working in healthcare supply chains were working exceedingly hard to keep our heads above water.

Look to our own practices in hospitals. Are meetings occurring with lots of people for a prolonged period of time without PPE? Breakroom clusters of staff to eat? Exposure is not limited to the patient-caregiver interaction.

Healthcare workers often have the foresight to know when patients are positive, while knowledge of cases in the community is less likely.

For many infection preventionists (IPs), hand hygiene in healthcare facilities is often subpar. National compliance rates tend to fall well under 50% and even with interventions, sustainable improvement is a unicorn IPs are always in search of.

As an infection preventionist, I found these to be helpful in establishing plans, training methods, and more.

Although all patients require vigilant infection prevention measures and the goal should always be zero infections, the stakes are sometimes higher in the NICU, as infections there have higher potential for death.

Exposure work-ups often involve tracing the movement of the patient and identifying staff who might have been exposed. But with COVID-19 is that feasible?